Rapid Growth:

1954-1964

Legacy of Leadership

This part of Barton Malow’s heritage story was written by former President and Chairman Ben Maibach Jr. in the late 1990s prior to his death in 2011. Ben Jr. had the privilege of working closely with Carl Barton and Arnold Malow and speaks to their impact on the values that shaped our culture in the early days of the company.

In the fall of 1954, Arnold Malow suffered a crippling heart attack, which required him to have a long period of convalescence. He spent the winter and spring of 1954-55 in Florida. Unquestionably, the strain of expanding operations had taken its toll on our President.

During this fourth decade, the continuity of the company was ensured. A new management team was put in place and the vision of the company changed to a much broader scope as far as market diversification and geography were concerned.

The Michigan Mutual Liability office building in downtown Detroit was probably the first high-rise structure the company built. My father, Ben Sr., was Superintendent on this building, and because of the proximity of adjacent high-rise buildings, the displacement of earth caused by the driving of piles resulted in some of the structures starting to rise. An innovative technique was used to correct the problem. A long cylinder was driven into the earth where the pile was to be placed. This was then extracted by forcing clay out of the cylinder with air pressure from the top end. The pile to be driven was then dropped down into the void created about half the length of the pile into the firm earth below: a simple but satisfactory method to resolve what could have been a serious problem.

Unfortunately, Arnold Malow never fully recovered from his heart attack. Despite this, he never lacked courage or enthusiasm. Without his financial strength, support, and counsel, the firm would have floundered. He provided the stability we needed even though he wasn’t really running the firm.

The four managing officers had a buy and sell agreement, which included a provision that if, for any reason, any one of us was separated from the company, we would be required to immediately sell our stock back to the corporation. Carl Barton, very distressed over Arnold Malow’s illness and other problems that had arisen, presented his stock he purchased in 1949 for $50,000 to the corporation in 1955 for $500,000. Although the price was at a premium, we believed he was entitled to this settlement. We agreed to a five-year window to retire this debt. His $50,000 investment in a five-year period had grossed him over $1,000,000, including profit sharing and wages.

Carl retired as Board Chairman and Director on May 31, 1955, which allowed him to take a more active role in the pursuit of the development of his personal real estate holdings, which had appreciated dramatically, and also to grant him more time to devote to community organizations with which he was affiliated. Carl Barton was really the founder and father of our company and the author of many of the philosophies and principles that we continue to exercise today. He was a very fair and honest man who I highly respected.

Automotive Success

We were extremely fortunate to develop a relationship with Cadillac Motor Car Company, which was essential when the Packard account was impacted by a merger with Studebaker, which eventually closed operations. Through the struggles of 1955, the volume dropped nearly a third to $12,000,000. We were fortunate enough to enjoy a small profit.

In 1956 we had a modest rebound and paid a dividend of $450,000. The return to the shareholders was 26%. Fortified by these achievements, we created a Rigging division to further accommodate our clients and diversify our services. Several of our clients called upon us on a 24-hour, seven-day-a-week basis to handle any emergency. Working crews 24-hours became a way of life and paid handsome dividends.

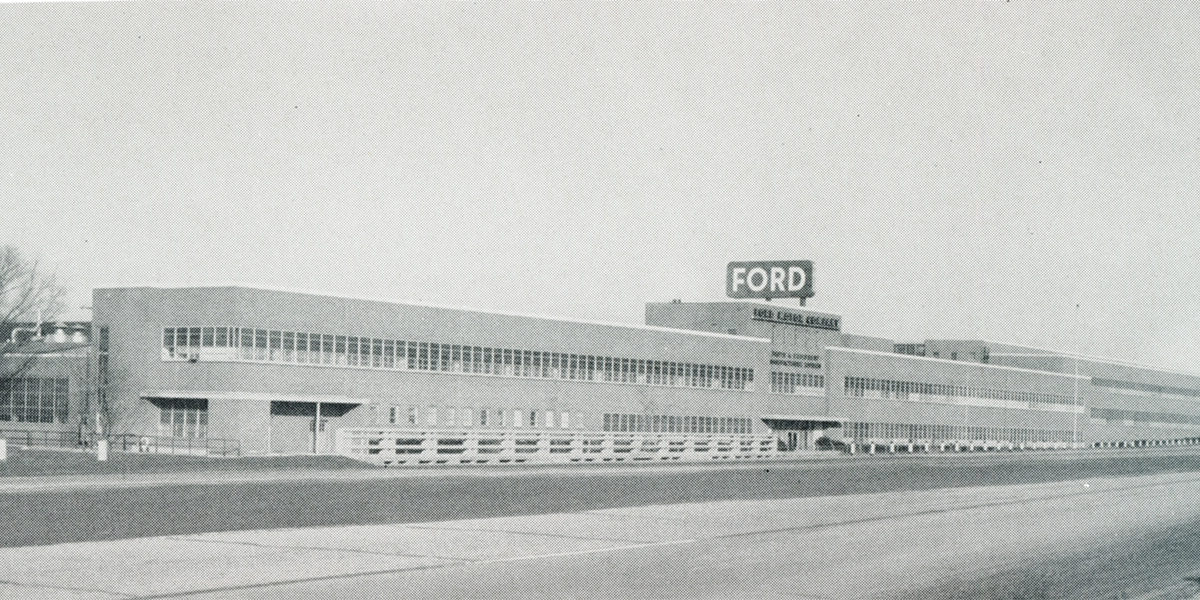

With Turner Construction Company of New York, we formed a joint venture to construct a parts and equipment manufacturing plant in Ypsilanti, Michigan, for Ford Motor Car Company. I believe this was the first joint venture project the company was involved in.

Ford Motor Company Parts and Equipment Manufacturing Plant in Ypsilanti, Michigan - 1950s

Arnold Malow’s age and declining health motivated him to offer all of his stock holdings to the corporation. His main concern was that we have the ability to pay off the debt and not be a burden to the company. He assured us that he would be as flexible as necessary. He insisted interest owed him would be less than that charged by our agreement with Carl Barton, which was generous of him.

I was 36 years old when Arnold sold his stock, and the thought of continuing our operations without C.O. and Arnold gave me great concern. I had a wife and six children to support at the time. That, on top of the responsibility of managing the firm and serving as a church minister, was overwhelming. The banks were very understanding and tolerant. Thankfully, they had confidence in the firm because of our earnings record and reputation in the community. On July 1, 1957, an agreement was reached that provided for the company to purchase Arnold Malow’s stock over a five-year period at 5% interest. Our annual yield upon investment for the eight-year period during this time averaged nearly 30%.

Diversification and Record Contracts

In recognition of our greater diversification, we were awarded a contract by Jones & Laughlin to modernize and enlarge a stainless steel sheet and strip mill in Louisville, Ohio. Parke Davis & Company, later a part of Warner Lambert, and Pfizer, awarded us a contract for their new research laboratories and offices in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

This was our first contract in excess of $10,000,000. My hand actually shook as I signed the contract. Later in discussing this with my dad, he thought we were being extremely risky. Volume escalated in excess of $16,000,000 with an earnings record of $139,000.

In 1958, Parke-Davis awarded us a second contract to build an office and warehouse in Skokie, Illinois. It was a unique project. Yamazaki was the architect and the bid documents called for a folded plate sawtooth roof to be either poured in place or prestressed concrete. Yamazaki was an innovator of the precast method and he had a relationship with Basalt of California, who was supposedly an expert in the field.

Due to the length of the folded plate roof members, it was necessary to cast and prestress them at the jobsite. To the dismay of all, after the pours were made under the direction of the architect and engineers, every section was too short due to shrinkage and prestressing. After remedial work, the engineers accepted the panels with modifications. During the erection of the leaves, temporary shoring was placed. The top and bottom edges of these folds had embedded angles and were welded together during construction. When the shoring was removed, one of the sections failed, causing a domino effect on the other sections. In just a matter of minutes, the whole roof collapsed.

God looked down kindly upon us and spared us from a major disaster. The roof collapsed near quitting time when most of the workers were out of the building. Fortunately, a truck and a crane inside the building helped support some of the roof and allowed people to escape. It was a miracle that no one was killed or seriously injured. Obviously, we had a very serious problem on our hands.

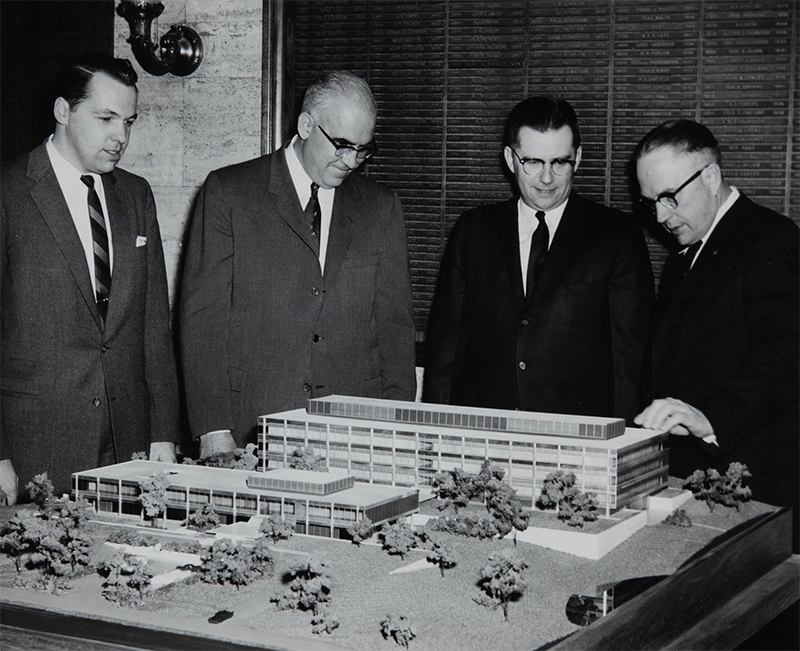

Parke-Davis Laboratory Building West Model - 1958

Through this experience, I learned a very important lesson. In a meeting with the owner, architect, engineer, subcontractors, and insurance companies to resolve the problem, it became obvious that there was a lot of finger-pointing. An amicable solution seemed unlikely from the tone of the meeting. I personally met with the representatives of all concerned firms and recommended that we accept responsibility jointly, and pool our resources to fix the problem in lieu of spending a lot of money in court which would have only delayed the project and would have been extremely costly. Gratefully, reasoning prevailed and, in very short order, the roof was re-constructed and we continued on our way.

My role in this settlement played a large part in my being elected to the Board of Directors of our insurance carrier, Michigan Mutual Liability Company, now Amerisure.

Volume grew by $1,000,000 and profits by about 30%. On June 1, 1959 we entered into a contract to construct a U.S. post office in Detroit, which at that time was the largest building in cubic feet in the State of Michigan. The approximate cost was $23,000,000. Floyd Wieland was the Project Administrator. This building, with a very tight schedule, was completed in record time and very dramatically enhanced our image in the industry. Unfortunately, my father, one of the oldest employees of the company, suffered a fatal heart attack while working on this job.

The U.S. Post Office project in Detroit was, at that time, the largest building in cubic feet in the State of Michigan - 1959

It has been wisely said that nothing is more vulnerable than entrenched success. Growing too fast, combined with operations in remote areas and becoming involved in new types of construction employees were not familiar with, almost caused disaster.

In Marquette, Michigan, with Bechtel Corporation as the engineer, we were to construct a pelletizing plant for the Empire Mine. We soon learned that pouring concrete in rock and tunnel excavations was not our forte. We also had three contracts with Oakland County, Michigan, to construct a large part of the 12 Town Relief Drains. These cast-in-place storm sewers were large enough to drive automobiles through them. Unfortunately, unseasonable torrential rains flooded the excavations and complicated an already tense situation. We were able to finish the projects wiser, but much poorer. Volume shrunk $5,000,000 to just above $12,000,000, but we were able to maintain a slight profit of $92,000.

My partner, Harold Butler, who shared 50% of the ownership of the company with me, had an aneurysm. During his convalescence, I visited him in the hospital and was shocked to learn he wanted to retire and offer his stock for sale. His father had died relatively young from an aneurysm and he feared this would be his fate too. Our $15,000 original investment, in spite of the buyout of the two senior partners, was now a considerable sum. The corporation was not in a financial position to redeem Harold’s stock.

Harold Butler (left) next to Ben Maibach Jr. at his retirement party - 1962

On April 1, 1960, I made arrangements for Rolland Wilkening, a Purdue University civil engineer graduate who had started work for the company in 1950, to purchase 40% of Butler’s stock. I guaranteed the debt and acquired the remaining balance, which gave me 80% ownership of the company. From my holdings, I sold a portion amount of stock to eight other company employees.

Harold Butler retired completely from the company in June of 1962. He retired early because of his concern for his health and yet he lived to be over 100 years old.

The company had always been active in Associated General Contractors. Carl and Arnold had both served as President of the state chapter, and I was also elected to the presidency. Our firm remains an active member of AGC today and has had many officers hold board positions at state and national levels.

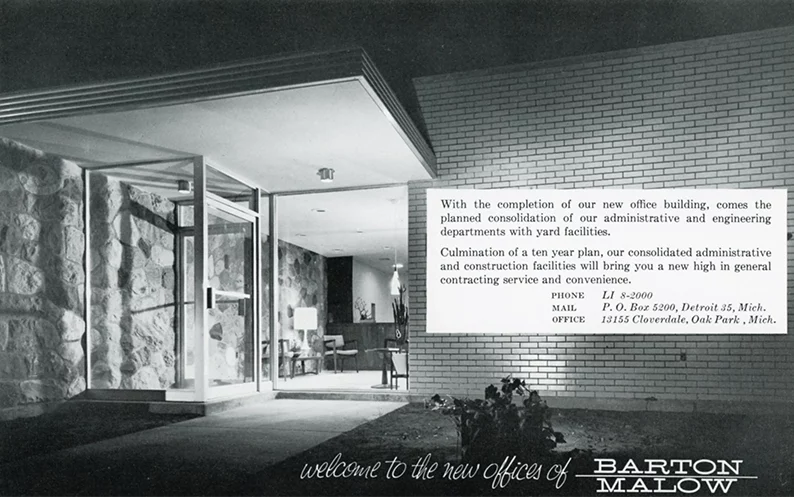

In April 1961, we moved into new offices at 13155 Cloverdale, Oak Park. Michigan Architectural Forum magazine reported that our volume for general contractors in 1961 had placed us 35th in the nation and second in the State of Michigan. On a volume of $9,679,000, we had a net earning of $131,000.

Rapid Expansion

1962 was a banner year — the Jefferson Apartment Building, 27 stories plus penthouse, was the tallest reinforced concrete structure in the State of Michigan. We had ongoing contracts in Alpena, Michigan, with Abitibi along with Huron Portland Cement Company, where we installed several kilns while simultaneously working with Peerless Cement Company in Detroit. In Fort Wayne, Indiana, we built the St. Joseph Hospital.

The backbone of our success, however, was long-term relationships with firms such as Kelsey-Hayes, Cadillac Motor, General Motors, National Steel, Difco Laboratories, Union Carbide Company, General Electric, Alcoa, Standard Oil, and many others.

Personally, our family had grown to seven children, two boys and five girls. The company was expanding rapidly. I was doing a lot of international public speaking along with added responsibilities in my church as a minister and served on numerous community boards. My nature was to make fast decisions and most of those decisions were good, but unfortunately, I also got careless. In 1963, all of the profits that had been gained in the three previous years were almost eradicated. Since the 1949 reorganization, 1963 was the only year the firm found itself in a loss position. Arnold Malow kindly rose to the occasion and agreed to postpone the payment of monies owed to him for his stock for another year. It allowed the firm to regain its equilibrium.

Adversity is not always bad. The mettle of an organization and individual strength is manifested when problems arise. 1963 was one of the most educational years I have ever had. Thanks be to God that 1964 was a turning point and better things were on the horizon. Ford Motor Car Company awarded us a contract in 1964 to build a 2.6 million SF stamping plant in Woodhaven, Michigan, which gave us the opportunity to prosper.

Lee Iacocca, Vice President of Ford, is acknowledged as the father of the Mustang, and he wanted to get his brainchild into production. We were brought in to help develop innovative ideas to expedite the construction of this facility in record time.

This project was the first fast-track or construction management job the company managed. Working in close concert with Ford and the architect, Albert Kahn, we used every possible method to expedite the construction. When actual production started in the front of the facility, we were still completing a portion of the rear section. Results were satisfactory and rewarding. The success of this project propelled Barton Malow as a construction management delivery innovator.