Leading the Industry:

1964-1974

Legacy of Leadership

This part of Barton Malow’s heritage story was written by former President and Chairman Ben Maibach Jr. in the late 1990s prior to his death in 2011. Ben Jr. had the privilege of working closely with Carl Barton and Arnold Malow and speaks to their impact on the values that shaped our culture in the early days of the company.

In 1964, Rollie Wilkening was promoted to Executive Vice President, two new Vice Presidents, Floyd Wieland and Eugene MacCracken were elected to help oversee field operations, and Robert C. Mair continued as Treasurer of the company. At year end volume had exceeded $30,000,000, new vision was established, and a modest profit of $138,000 was achieved. This revitalization is an important cornerstone and 1965 saw volume continuing in excess of $27,000,000 with net earnings of $239,000.

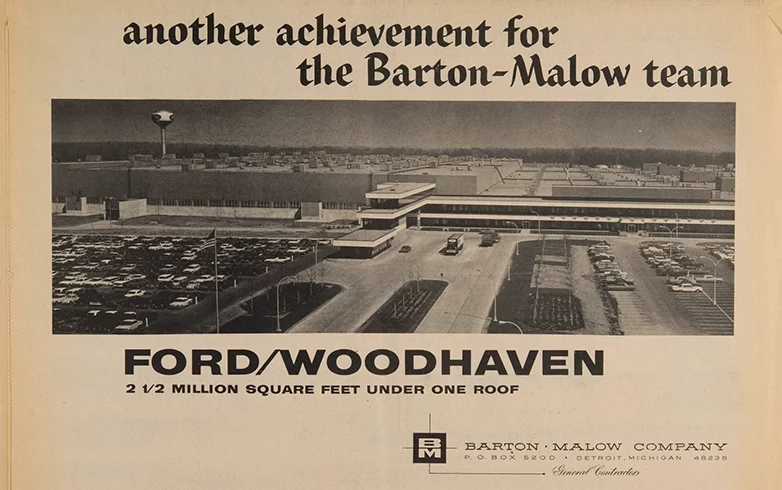

The Ford Woodhaven Stamping Plant project, completed in the early 1960’s for the Mustang, went exceptionally well. The new construction management delivery system was used to bring about more cooperation between the owner, architect, engineer and contractor. Barton Malow is proud to be one of the first to recognize the value and the benefits of this methodology.

News clipping from The News-Herald - 1966

Diversification continued and our identity in previous years had been closely associated with the steel industry. The Federal Mogul Corporation granted us the opportunity to erect their new corporate headquarters in Southfield, Michigan.

Significant projects built during this period were the Detroit Institute of Arts and Cultural Center south wing on Woodward Avenue in Detroit and a year later in 1966 we constructed the $7,500,000 north wing to this beautiful edifice.

Another interesting contract was the rehabilitation of the General Motors Building in the New Center area in Detroit. Our company painting division revitalized the entire exterior of the structure. Amerisure was so impressed they called upon us for the exterior restoration of the old Stroh Building in downtown Detroit for their main office.

In 1966, Arnold Malow retired as a board member and director. As a token of appreciation for his outstanding leadership we gave him a new Lincoln Continental. It was no coincidence that the car was a Ford product due to our involvement with Ford on the Woodhaven project.

In December 1966, we had groundbreaking for the Henry Ford Centennial Library in Dearborn, Michigan. I remember vividly during the initial stages of construction a 126-foot boom on the pile driving rig collapsed, causing damage in excess of $250,000. When the crane toppled, the boom fell almost directly on the operator’s seat of a giant earth mover. While it was tilting, the workmen screamed, alerting over a dozen workers who scattered with only seconds to spare. Adding to the commotion, the ruptured gas tank on the crane burst into flames engulfing the earth mover. Amazingly enough, no one was injured. It was a reminder to redouble our attention to safety.

The company has always prided itself on its clientele of Fortune 500 companies who have awarded us repeat work on an ongoing basis. One example was Parke-Davis (later part of Warner Lambert and now merged into Pfizer) who favored us with a contract for their Pathology and Toxicology Labs in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Sales for 1967 broke all company records, more than doubling any previous volume; revenue was $78,000,000 with profits at a 32% yield on investment. This added volume necessitated the addition of approximately 6,000 SF to our Oak Park office building.

It was a banner year. I received the Governor’s Award in the Michigan Minuteman Honor Program, which honored the person who had done the most to promote construction. George Romney, then Governor of Michigan, made the presentation on my birthday, May 24, on the steps of the State Capitol Building in Lansing.

During that year we also built a 14-story, low-income housing project in Lincoln Park, the first building in the Detroit area since 1954, using only federal grants. Other high-rise projects came into being as we built the Hoyt-Pittman-Hill Residence Halls for Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti.

We continued to enjoy a positive relationship with Ford Motor Car Company as we were awarded several projects, which included the Experimental Diagnostic Center in Dearborn, Michigan, a large addition to the Body Engineering Building at the Research Engineering Center, an addition to the Wayne Assembly Plant and a Parts Depot in Memphis, Tennessee.

Arnold Malow had been a Director of Children’s Hospital for many years and the company had rendered a lot of service as a maintenance contractor. On July 26, 1967, we had a groundbreaking for the new six-story hospital, replacing the old structure that had served them for many years. We purchased a child’s pedal tractor and trailer, painted it in company colors and inscribed it with our logo. An eight-year-old patient of the hospital sat on the tractor while some of the Trustees broke ground, placing the dirt in the trailer.

This hospital was rather unique as the foundation was a single concrete mat approximately three feet thick, totaling over 8,500 cubic yards. The reinforced concrete structure allowed us to introduce a different method of placing concrete, as we were successful in pumping low slump concrete to the roof of the six-story structure effectively at a rate of about 50 yards per hour with new concrete pumps. We were so pleased with the results that we purchased three of these machines. Financially, the project was a not a success as we lost over $300,000, but we all recognized it was for a good cause. Part of the project loss was due to a crippling strike. The sheet metal unions were trying to penalize an out-of-state contractor who was one of our subs on the job.

The scriptures fulfill themselves, “All things work together for good according to his purpose for those that love the Lord,” for a few years later, a critically ill granddaughter was rushed to Children’s Hospital, and God miraculously provided for her complete recovery. Here again the scripture, “Cast thy bread upon the water; for thou shalt find it after many days,” was certainly magnified in that experience.

The construction industry as a whole did not enjoy a very good record as far as safety was concerned. In recognition of the need to improve safety performance, we were pioneers in forming the first construction division of the Michigan Safety Conference. We also helped to mold the construction division of the Detroit Safety Council. I was elected Chairman of the Construction Division for the Michigan Safety Conference in 1968 and served as a director of both the Conference and Council for many years.

Volume for the year 1969 was over $66,000,000, 1970 over $59,000,000 and 1971 over $73,000,000. Our volume was beginning to hold quite steady and profits were remarkable. The company’s net worth was over $2,400,000, which in those days was quite impressive.

In 1968, we ventured into South America at Asuncion, Paraguay, to explore the possibility of erecting a multi-story reinforced concrete marketplace. A major New York accounting firm we were working with, instructed me there would be two sets of books, one actual and one showing a so called 10% “business tax” that was paid to the officials that we had to work with. Apparently, that was common practice in South America. I could not support paying off officials and immediately broke off all negotiations. The marketplace was never built.

Expansion Out of Michigan

The 60’s provided opportunities for a lot of change. In the Detroit area, almost yearly, we encountered a major strike of one of the building trades. After a lot of consideration, we agreed to expand out of Michigan and, in 1968, acquired Mead & Mount Construction Company of Denver, Colorado. The firm had been founded about the same time as Barton Malow and had approximately the same net worth. Its principal, Roger Mead, died rather unexpectedly and the terms of his will required either the outright sale of the company to others outside of the firm or its liquidation. The only costs for this acquisition were expenses concerning the purchase plus a small binders fee, a far cry from the complexities of today’s mergers.

In Denver, we completed the United Airlines Training Center, which was used by many of the second-world nations to train their pilots. We also constructed a hangar for United at Detroit Metro Airport, now used by Delta. This started a trend with work at the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and also hangars for Frontier and Western Airlines at Stapleton Airport near Denver. In the west we expanded our construction management expertise and built a large complex for Western Electric, just north of Denver. When we acquired Mead & Mount they had a subsidiary in Wyoming and we did several buildings for the University of Wyoming.

United Airlines Training Center in Denver, Colorado - 1970s

In the Colorado area, several hospitals were added to our list, including University Hospital, Beth Israel Hospital in Denver, Poudre Valley Hospital, and Methodist Hospital in Omaha, Nebraska. We continued to do a lot of work at Colorado State University.

Continuing our finesse in water treatment and disposal areas, we constructed a huge complex for the Metropolitan Denver Sewer System, an addition to the building the firm had originally built.

Meanwhile, back in Michigan, we continued to move forward and constructed facilities for the U.S. Postal Department in Saginaw and Dearborn, Michigan. During this period, we entered into a contract with the Burroughs Corporation to build their world headquarters in the New Center in Detroit, Michigan. This 600,000-SF building was unique because a five-story manufacturing plant was to be transformed into a very modern sophisticated office structure. Unfortunately, the architect was a very small firm with inadequate expertise and the scope of the work was far beyond their capabilities. This resulted in a project delay of over a year. Several of the subcontractors threatened suit because of the costly and unusual delays and the excessive number of change orders, which totaled over 500.

For the second time in the history of the company, we became involved in a lawsuit with our client. After extended negotiations that were unsuccessful, we started suit and finally, after several years, and only after we were in court, were we able to resolve this dilemma. A lesson derived from this experience is that in legal disputes, only the attorneys make money.

In 1970, the firm was engaged in the building of a transfer station for the U.S. Disposal Company. Unfortunately, that company had financial difficulties and fell into default. We finished the project, assumed U.S. Disposal’s contracts, and ran the operation as a wholly-owned subsidiary for several years until it had a successful track record. In 1973, we were able to get out of the disposal business by selling it, including the buildings and land, for a substantial profit to Browning Ferris, a national corporation with expertise in this field.

On my birthday, May 24, 1971, Arnold Malow passed away at the age of 78. I reflect on how fortunate we were for his generosity and vision and his allowing an orderly transition of company ownership. I learned a great deal from the founding fathers Carl Barton and Arnold Malow. The integrity they demonstrated had a lifelong impact on me and the company.

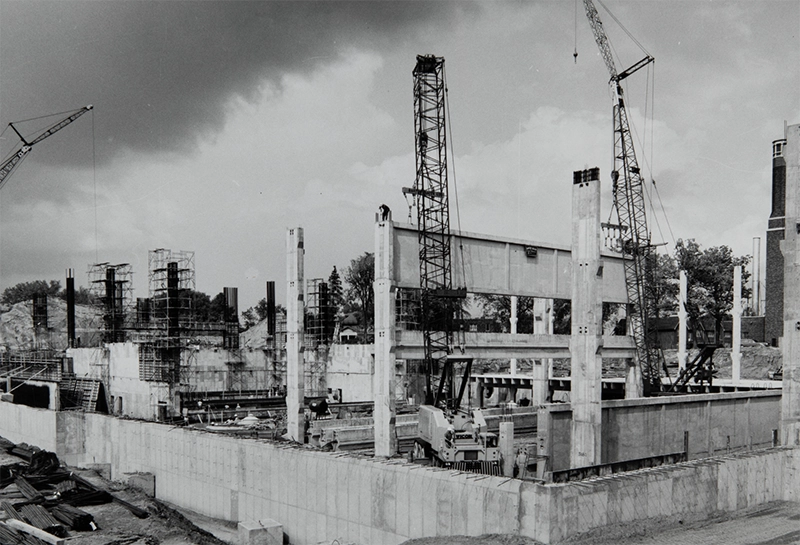

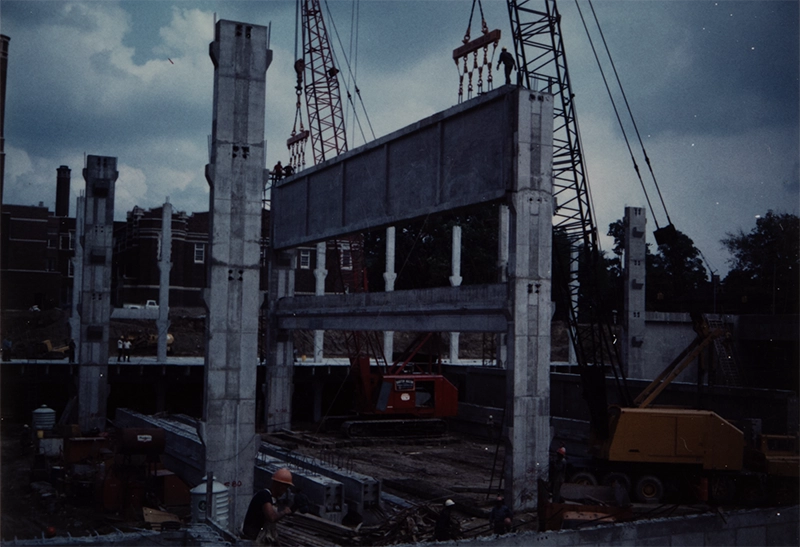

At this time, there was national interest in the new construction at Pontiac Central High School in Michigan. This 390,000-SF building had a revolutionary concept and design, recognizing another step forward on fast-track contracting. The project was bid competitively with only preliminary plans and specs. The only detailed drawings at that time were for the underground work. Precast concrete post tension girders 100 feet long and 16 feet high, weighing over 160 tons, were cast on the site and lifted into place. It was estimated that at least six months of construction time was saved on this $14,000,000 project, which was ready for occupancy in the fall of 1972. This project elevated Barton Malow on the national construction management stage since it was the feature of case studies and the results were widely published.

Our association with William Beaumont Hospital has been a pleasant one of longstanding and continued with the construction of an $11,000,000 West Wing addition to their Royal Oak, Michigan, facility. In 1973, the hospital announced that we were selected as the general contractor for a $22,000,000, 200-bed hospital facility in Troy, Michigan. Today, William Beaumont Hospital remains a valued client.

Leading the Industry with Construction Management

Inflation was rampant in the 1970s. Because construction costs began to escalate at approximately 1% per month, projects were consistently running over budget. The General Services Administration, in an attempt to find a solution to control this unfortunate situation, asked Rollie Wilkening, then Executive Vice President, to serve on a special committee of the Associated General Contractors of America to study the construction management method and determine whether or not the delivery method was viable. Rollie saw the potential to sell the delivery method Barton Malow had early experience with, and he began to speak on the merits of construction management to various professional groups across the country. In addition, he wrote several articles for national publication. In 1973, he delivered a presentation at the National AGC Convention.

This was personalized, incorporating Barton Malow’s CM experience, and was a very successful tool in selling our services. At the time, we had very little competition for CM work, primarily because our competition thought the delivery method was a passing fad. We were leading the industry. We brought on board several electrical and mechanical engineers as well as architects to critique, design, and provide technical support in conceptual estimates for this new venture, advancing the concept of value engineering.

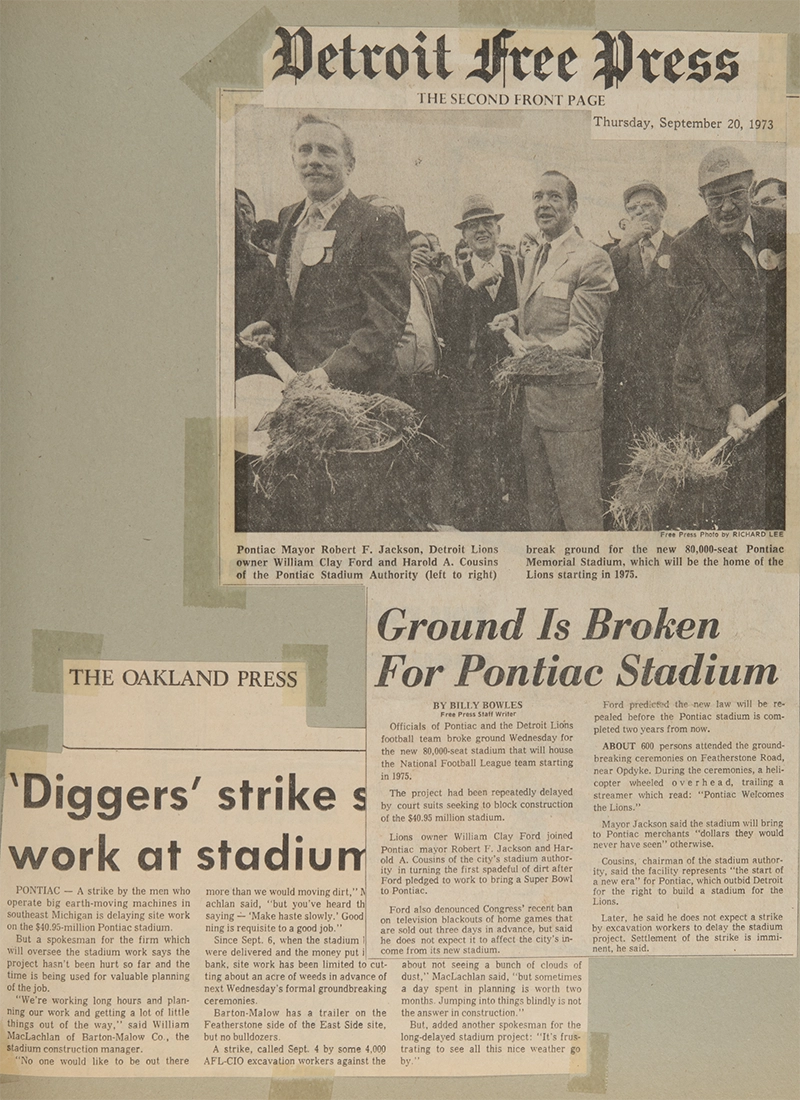

An innovative project challenge the firm accepted was the one that received significant notoriety and established the trademark slogan: “On time and under budget.” The project was the Silverdome stadium. The air-inflated roof of over 10 acres with a seating capacity in excess of 80,000 people received international acclaim. When we undertook the risk for the inflated roof, guaranteeing the results, we borrowed $7,500,000 with the understanding we would not be paid until it was inflated and accepted by the stadium authorities. The air-supported fabric roof was new technology, which had never been used on this scale. We were paid in full.

Most stadiums built during this time period were plagued with schedule delays and cost overruns. When the Silverdome was completed profitably and on time, the national recognition opened many doors. Fast-tracking techniques were brought into very clear focus and this project launched Barton Malow into the national sports market.